Chandler’s novels were soon made into films, and Chandler also worked as a screenwriter in Hollywood. Some the films based on his novels and on his screenplays became classic film noir. Most of these films are now available online thanks to archive.org and other websites, but they may take a few seconds to load. If you interested in films adapted from Chandler’s novels, I highly recommend Stephen Pendo’s book.

| Year | Films adapted from Chandler’s novel | Screenplays by Chandler |

|---|---|---|

| 1942 | Time To Kill (The High Window) The Falcon Takes Over (Farewell, My Lovely) | |

| 1944 | Murder, My Sweet (Farewell, My Lovely) | And Now Tomorrow (with Frank Partos) Double Indemnity (with Billy Wilder) |

| 1945 | The Unseen (with Hagar Wilde) | |

| 1946 | The Big Sleep | The Blue Dahlia |

| 1947 | The Lady In The Lake The Brasher Doubloon (The High Window) | |

| 1951 | Strangers On The Train (with Czenzi Ormonde) | |

| 1969 | Marlowe (The Little Sister) | |

| 1973 | The Long Goodbye | |

| 1975 | Farewell, My Lovely | |

| 1978 | The Big Sleep |

The very first two films adapted from Chandler’s novels were anything but film noir and mercilessly exploited Chandler’s novels. Most notably, they simply omitted the archetypal character Philip Marlowe to replace him with the private eye Michael Shayne in Time To Kill and with the character Gay Lawrence aka the Falcon, a gentleman detective wearing a silk scarf and a tuxedo in the The Falcon Takes Over. Since both the protagonist Philip Marlowe and his narrative voice are an integral part of Chandler’s novels, these two films are mentioned here only for the sake of completeness.

Murder, My Sweet and The Big Sleep, however, are definitely iconic film noir that helped to define the entire genre.

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

I like Murder, My Sweet for its stylish noir look, Dick Powell’s voiceover and retrograde storytelling. The director of the film Edward Dmytryk later realized: “There’s no question that Murder, My Sweet started a trend, set a style that was continued up to the present day.” (Duncan & Müller, p. 309). Cameraman Harry Wild used low-key lighting that created spectacular Chiaroscuro effects influenced by German expressionist films.

There is also a great surrealist sequence in Murder, My Sweet: The drug-induced nightmare.

The only drawback for me personally is the character Anne Riordan. As I have pointed out in my blog post about Anne Riordan, she has never been shown in a film the way Chandler intended the character to be. In the film Anne Riordan had been changed to Ann Grayle, the stepdaughter of Helen Grayle aka Velma Valento, the murderous femme fatale. In his article “Anne Riordan: Raymond Chandler’s Forgotten Heroine” David Madden calls it “the alteration of Anne Riordan into a model of daughterly love and rectitude” (p. 10).

The Big Sleep (1946)

The other essential film noir based on Chandler’s novels is The Big Sleep (1946) starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. There are many articles about the relationship Bogart and Bacall that I won’t bore you with again here. But their romance in real life influenced the production of the movie. The changes in the script and the additional scenes which were shot eight months after the original version was completed made the plot of the film even more incomprehensible than the novel and its now legendary plot hole: Who killed Owen Taylor?

The first version of the movie was previewed by “servicemen overseas in the early fall of 1944 (…), a common practice during the war”. (Pendo, p. 46) After Bogart’s and Bacall’s wedding on May 25, 1945 Warner Bros. called for more scenes of their flirty banter which were added in 1945. If you watch closely, you can tell which scene was shot in 1944 or in 1945. What was left on the floor of the cutting room is the scene at the D.A.’s office (chapter 18 in the novel) that would have really helped the audience understand the plot.

It seems as if most of the scenes with Martha Vickers had also been cut out so as not to overshadow the leading actress Lauren Bacall, who had not yet had any acting training at the time. But you can still imagine how Vickers could have easily outshone Bacall if you watch the scene at Joe Brody’s apartment when she enters the room at approx. 00:53:00 and threatens Brody.

Due to the Hays Code director Howard Hawks was not allowed to show the pornographic nature of Geiger’s book store, the homosexual relationship of Geiger and Lundgren nor Carmen’s nudity at Geiger’s place. This confused the audience even more and made the film harder to understand. It is interesting to compare the two versions of films: the pre-release and the theatrical release.

The two film adaptations of Chandler’s novels from 1947, The Lady In The Lake and The Brasher Doubloon are disappointing and have left no lasting impression on viewers.

The Lady In The Lake (1947)

The Lady In The Lake was the attempt to transfer the first-person narrative of the novel to the medium of film with the help of the subjective camera which failed spectactularly. Director Montgomery, who plays the detective, or rather speaks, is only seen in the prologue, at most once in a mirror or a window pane, otherwise the camera completely takes the place of the detective. It follows every movement of the characters, Marlowe’s interlocutors stare into it, it is kissed, it smokes and occasionally gets punched in the lens. An experiment that could only prove what had already been suspected beforehand: an ambitious flop.

Even if it is not a “Chandler film”, Dark Passage (1947) starring Bogart and Bacall has to be mentioned here as well, because it also featured the subjective camera. But Director Delmer Daves avoided the mistakes Montgomery had made in The Lady in the Lake by varying the camera angle from time to time. Film critic Hal Erikson believes Dark Passage does a better job at using this point-of-view technique, writing, “The first hour or so of Dark Passage does the same thing—and the results are far more successful than anything seen in Montgomery’s film.”1

The Brasher Doubloon (1947)

The fourth film adaptation of Chandler’s novels from 1947 is The Brasher Doubloon, the second film version of The High Window after the half-hearted attempt to turn the novel into Time To Kill (1942). Pendo calls it “the only Marlowe film with a more confused plot than its source novel” (Pendo, p. 91) which does not suffer from such plot irregularities.

According to Pendo the film also tries to borrow elements from previous successful films, but fails to do so: on the one hand a fateful object that has been linked to the demise of its previous owners like The Maltese Falcon and on the other hand the love interest of The Big Sleep.

Pendo points out that the opportunity to dramaturgically enhance the meaning of the doubloon in the script was overlooked.

“As Morningstar tells Marlowe: ‘The man who coined it was murdered and robbed through the treachery of a female. Since then, at least seven other owners of the coin have come to abrupt unhappy ends.’ […] Very little use of the coin’s violent history is made. Even at the end of the picture, the audience is not reminded that the coin caused the Murdocks’ downfall. The opportunity exists, for Marlowe produces the doubloon to give to Mrs. Murdock. But the chance to stress the doubloon’s history is lost.” (Pendo, p. 94)

Love interest? Really?

The recurring problem of many films adapted from Chandler’s novels is that screenwriters invariably tried to introduce a love interest into the story – with more or less success. In The Lady in the Lake, however, this idea of adding a love interest is a complete failure. The love interest leads to obvious contradictions in the characterisation of Merle Davis, personal secretary to Mrs. Murdock. In the novel she is quite a complex neurotic character. She is definitely the least likely female character of Chandler’s novel to be turned into Marlowe’s love interest.

The result was the most un-Chandler-like female in any Marlowe film. The basic problem is that the reconstructed Merle simply cannot make up her filmic mind whether she has stayed the meek girl of Chandler’s novel who fears men, or developed into a sexual bombshell on the order of Lauren Bacall.”

(Pendo, p. 94)

Former boxer and stuntman George Montgomery’s rendition of Marlowe remains wooden throughout the film. He lacks the sarcasm and cynicism of Powell and Bogart, but sports a mustache and plays golf.

“His worst characteristic, both in the way the role is written and the way Montgomery plays it, is that, unlike the other film Marlowes, he isn’t really concerned with seeing justice done. He knows that if he solves the case, Merle’s fear of men will be removed and she will be open for sexual conquest, and this is his major reason for staying on the case.”

(Pendo, p. 96).

Ray as a screenwriter

“If my books had been any worse, I should not have been invited to Hollywood, and if they had been any better, I should not have come.”

Letter to Charles Morton (Dec. 12, 1945). In: MacShane, Letters. p. 56

From 1944 on Chandler started working as a screenwriter in Hollywood. He wrote and co-wrote the scripts for five movies of the Film Noir era. Double Indemnity that he co-wrote with Billy Wilder is often called one the best film noir ever and was nominated for Best Screenplay at the Academy Awards 1945. Chandler’s first original script for The Blue Dahlia earned him another Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay in 1947.

Double Indemnity (1944)

Although being a great success the collaboration of Wilder and Chandler was extremely difficult. Chandler complained in a letter to the producer about Wilder drinking alcohol in the office, wearing a hat indoors (Wilder wanted to cover a bald patch), talking to the girls he dated on the phone. After Double Indemnity they would never work together again.

The film The Blue Dahlia (1946), Chandler’s next screenplay, was influenced by WWII in multiple ways.

The Blue Dahlia (1946)

Paramount had a very popular team leading actor and actress at that time, with a similar chemistry on the screen as Bogart & Bacall: Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.

But the problem was that in 1945 Ladd “was called up to fight. (…) They needed to find Ladd a movie to make before he left for basic training.” (Williams, p. 211) And one might add: They had to shoot the film in a very short period of time.

One of the producers, John Houseman, wrote an essay titled “Lost Fortnight” on Chandler and The Blue Dahlia for Miriam Gross’ The World of Raymond Chandler. He and Chandler had become friends during the production of The Unseen (1945), probably because they both attended English public schools. Now Houseman was rather desperately looking for a script when Chandler told him during lunch that he had started another Marlowe story. He complained that he got stuck after 120 pages and “was seriously thinking of turning it into a screenplay for sale to the movies”2. Houseman wanted to see what Chandler had written so far and was so impressed by what he read that Paramount commissioned Chandler to write the screenplay of the next Alan Ladd film forty-eight hours later.

At first Chandler was exhilarated at the prospect of writing an original screenplay without any interference:

“I am very busy doing an original screenplay which is much more fun than anything I have done in pictures so far because instead of fighting the difficulties of translating a fiction story into the medium of screen, I can write directly for the screen and use all its advantages.”

Letter to James Sandoe, February 10, 1945 (quoted by Williams, p. 213)

Due to the tight time frame, filming began before Chandler had finished the script. The film crew, however, were able to shoot the scenes faster than Chandler was able to produce new material.

“By the end of our first week we were a day and a half ahead of schedule. In the next fortnight we gained another day. It was not until the middle of our fourth week that a faint chill of alarm invaded the studio when the script girl pointed out that the camera was rapidly gaining on the script. We had shot sixty-two pages in four weeks; Mr Chandler, during that time, had turned in only twenty-two – with another thirty to go.”

(Houseman in Gross, p. 58)

Originally Chandler had wanted to address PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) by making the character Buzz Wanchek the murderer of Helen Morrison. In the film Buzz played by William Bendix still has a shell fragment in his skull and suffers from a chronic condition that causes him to experience migraines and memory loss. He also has frequent blackouts when exposed to certain types of loud music or sounds.

The US Navy, however, insisted on changes to the plot, saying that it would be really bad for morale in the armed forces if a naval officer who was mentally hurt committed a murder. So, in the final version of the film, it was actually the hotel detective who was the killer.

The changes to the script really upset Chandler:

“What the Navy department did to The Blue Dahlia was a little thing like making me change the murderer and hence make a routine whodunit out of a fairly original idea.

(Letter to James Sandoe—June 17, 1946)

Similar to the disputes with Billy Wilder while working on Double Indemnity, there were also conflicts with colleagues while working on the screenplay for Blue Dahlia. He called Alan Ladd’s co-star “Moronica”3 Lake.

Strangers On A Train (1951)

Chandler also got carried away when working on the next script of Strangers On A Train. Chandler eventually called the director Alfred Hitchcock a “fat bastard”4.

Hitchcock decided not to work with Chandler anymore and recruited a new screenwriter Czenzi Ormonde to write the final script. After all, Chandler had only been Hitchcock’s second choice after Dashiell Hammett. Hitchcock is said to “have made a great show of holding his nose as he held Ray’s draft in his forefinger and thumb before dropping the pages into the bin.”5 Nevertheless, Ormonde left some of Chandler’s scenes in the final script, for example the famous opening shot tracking the feet of the protagonists until they meet.

As Chandler’s name is “all he had ever really wanted from Chandler all along”6, Hitchcock did not omit it from the opening titles.

Although Chandler was successful as a screenwriter and earned up to $4,000 a week, he had been disillusioned by the Hollywood system. In the November 1945 issue of The Atlantic, he expresses his frustration as a screenwriter, but also emphasizes how important a good screenplay is for a film:

“The making of a picture ought surely to be a rather fascinating adventure. It is not; it is an endless contention of tawdry egos, some of them powerful, almost all of them vociferous, and almost none of them capable of anything much more creative than credit-stealing and self-promotion. Hollywood is a showman’s paradise. (…)

For the basic art of motion pictures is the screenplay; it is fundamental, without it there is nothing. Everything derives from the screenplay, and most of that which derives is an applied skill which, however adept, is artistically not in the same class with the creation of a screenplay. But in Hollywood the screenplay in written by a salaried writer under the supervision of a producer—that is to say, by an employee without power or decision over the uses of his own craft, without ownership of it, and, however extravagantly paid, almost without honor for it.”

Chandler’s experiences in Hollywood inspired him to write The Little Sister which was not adapted to the screen until 1969. Pendo maintains that one “might propose that Chandler, unhappy with his experience in Hollywood, tried to develop a plot unadaptable to the screen” (Pendo, p. 117), including three different blackmailing schemes.

Modern adaptations: Neo-noir

To be honest, I don’t particularly like the modern adaptions in colour, maybe with the exception of The Long Goodbye by Robert Altman which seems to be an ironic parody at times. Robert Mitchum was 58 years old when Farewell, My Lovely was released in 1975, nearly twice the age of Philip Marlowe who is thirty-five years old in the novel The Big Sleep. James Garner’s Marlowe is too funny to be cool. But what intrigues me when watching these adaptions are the differences between the novel and the script and added characters that do not appear in Chandler’s novels. But let me discuss these movies chronologically.

Marlowe (1969)

Given the two-decade interval between the 1949 novel and the 1969 film, the screenwriter Sterling Siliphant faced the challenge of carefully modernizing the setting and characters while streamlining the intricate plot7 and taking out “Chandler’s bitterness towards Hollywood.” (Pendo, p. 124). The title of film was changed to Marlowe. The film was shot in color and with daylight, which obviously sets it apart from the film noir adaptations.

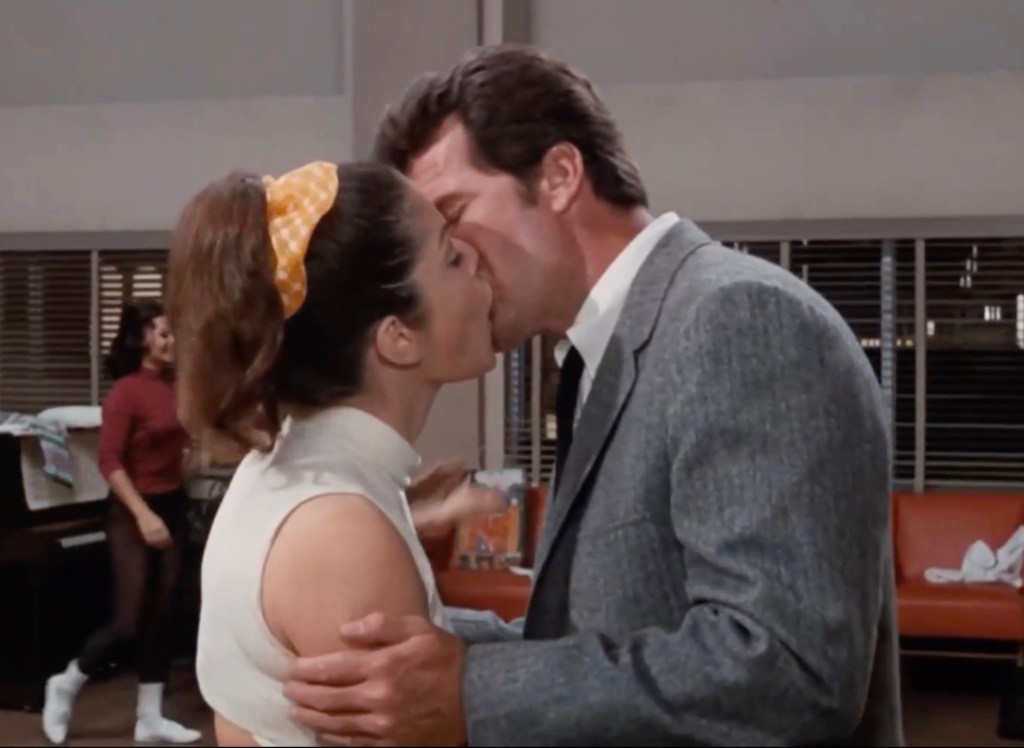

Siliphant added a few characters to his screenplay. Philip Marlowe played by James Garner now has a girlfriend called Julie played by Corinne Camacho.

A friendly neighbour at his office is a gay hairdresser called Chuck played by Christopher Cary. This is quite contrary to the fact that Chandler often portrayed queer characters in a homophobic way.

Please notice that James Garner and George Montgomery are the only Marlowes to smoke a pipe.

The film also marks the first ever appearance of Martial Arts legend Bruce Lee as Winslow Wong, a character that is not in the novel. He shows some of his famous karate chops, of course, wreaking havoc on Marlowe’s office furniture.

Chandler’s acerbic remarks about agents and studio bosses in The Little Sister were completely omitted from film. Siliphant also exchanged the movie industry for the TV industry. He added a scene that is quite remarkable and might be considered a subtle criticism of the TV business.

Marlowe has a conversation with a TV executive who he later accompanies to his private jet at the airport. They talk about the blackmail case while watching an ongoing show in the studio. They look at the monitors showing the program on air and a Great Garbo movie.

The ensuing dialogue referring to Garbo is not necessary for the plot and the investigation, but rather shows Marlowe’s nostalgic attitude.

Marlowe: She was great, wasn’t she?

TV exec: Oh yes! (…) The show we’re doing is out there.

The Long Goodbye (1973)

This nostalgic attitude can also be seen in Robert Altmann’s adaptation of The Long Goodbye. But unlike James Garner in Siliphant’ adaption of The Little Sister Philip Marlowe now played by Elliot Gould insists on wearing a white shirt and black tie at all times and drives a 1948 Lincoln Continental, Gould’s own car (Pendo, p. 155).

Gould’s Marlowe seems to be out of time. That was the way Altman intended the character to be:

“Marlowe is a Fifties character who has survived unchanged into the Seventies. He’s a man out of time, out of place. He wears white shirts, narrow ties, and rumpled blue suits with brown shoes. He is the only one in the whole picture who smokes constantly puffing on Camels or Luckies. For him, the last fifteen or twenty years never happened.” (Lipnick, p. 279)

Screenwriter Leigh Brackett had also co-written the script for The Big Sleep in 1944 and felt that a modernization was impossible. Brackett maintained that Marlowe could not be separated from his outdated context.

“By Chandler’s own definition, Marlowe was a fantasy. … He existed only in the context of the world Raymond Chandler especially invented for him… Take away that context, and who is Marlowe? Time had removed the context…. We’ve got a whole new generation and a whole new bag of cliches–just as phony but different.” (Brackett, p. 27)

The new generation are probably the lesbian nudist neighbors doing yoga topless and stretching their legs right in front of Marlowe’s apartment. The name of the criminal Mendy Menendez is changed to Marty Augustine who is a more modern mobster. One of his thugs is played by young Arnold Schwarzenegger sporting a moustache and yellow underpants. In a funny scene that is not in the novel Marty makes everyone undress to prove Marlowe has nothing to hide from him, except maybe a $5,000 dollar note.

Farewell, My Lovely (1975)

The 1975 adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely was also shot entirely on location in L.A., both for the exterior and interior shots. Pendo assumes that the great success of Chinatown (1973), which was also shot on location, may have been the reason to make Farewell, My Lovely a period picture (Pendo p. 178).

For the set design and the costume the producers took great effort to make the movie as “1941” as possible.

I already mentioned that Robert Mitchum was 58 years old when he started shooting the movie: too old to portray the character Philip Marlowe convincingly.

In the movie Farewell, My Lovely (1975) the character Dr. Sonderborg was changed to Frances Amthor played by Kate Murtagh, a lesbian butch who runs a brothel.

She is the one who drugs Marlowe in the movie.

Incidentally, four years later Murtagh became an icon of pop culture on the cover of Supertramp’s album Breakfast In America.

Jonnie, one of Amthor’s thugs is played by young Sylvester Stallone.

Jonnie is in love with one of Amthor’s girl. When Amthor find the two in bed, she hits the girl hard.

In a dramatic scene Jonnie shoots Amthor.

These plot changes obviously serve no other purpose than to show naked young ladies and the seedy side of L.A.

My favourite female character in Chandler’s novels, Anne Riordan, was completely omitted from the script and was replaced by a paper boy called Georgie. David Zelag Goodman who wrote the screenplay turned Marlowe into a baseball fan. Marlowe and Georgie repeatedly talk about Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak of 1941. When Marlowe manages to escape from Amthor’ place Georgie gives him shelter.

Charlotte Rampling as Mrs. Grayle is supposed to remind us of Lauren Bacall, but there is absolutely no chemistry between her and Mitchum due to the difference in age.

Other than that, I like the fact that the 1975 adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely does include the racial aspects of the novel. At the beginning of the novel Moose Malloy takes Marlowe to night club called Florian’s where his love interest Velma Valento used to sing before. During the time Malloy spent in jail this place has become a nightclub for people of colour. This fact is not shown in the 1944 adaption, but in the one from 1975.

The Big Sleep (1978)

The setting of the 1978 adaptation of The Big Sleep had been changed to contemporary Great Britain. The script closely follows the plot of the novel. Although some of the minor characters are prominently cast (James Stewart – General Sternwood; Joan Collins – Agnes Lozelle; Oliver Reid – Eddie Mars), the movie failed to leave an impression on viewers, because this setting simply did not work and Mitchum had turned sixty. It is too embarrassing to watch this movie again today.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_Passage_(film) ↩︎

- Miriam Gross (ed.), The World of Raymond Chandler. London 1977, pp. 54ff. ↩︎

- Tom Hiney, Raymond Chandler. A Biography. London 1997, p. 154. ↩︎

- Tom Williams, Raymond Chandler – A Life. London 2012, p. 274. ↩︎

- Williams, p. 276. ↩︎

- Williams, p. 278. ↩︎

- You can find a comparison between the novel and Siliphant’s script in Pendo, pp. 131ff. ↩︎

Leave a comment …