At Frankfurt book fair 2025, I spoke to Simone Menzies about Raymond Chandler. She told me that she had really enjoyed reading Chandler in East Berlin back in the 1980s. Never before had it occurred to me that Chandler had been read behind the Iron Curtain in the former GDR as well. After all, the USA was the “Klassenfeind” (class enemy) in the countries of the former Warsaw Pact. In fact, the GDR, or more precisely the publishing house “Volk & Welt”, which specialized in American literature, acquired licenses for the German translations from West German and Swiss publishers. (Chandler’s popularity in Germany can also be seen by the fact that Diogenes in Zurich has just published all of Chandler’s novels with new translations into German.)

Censorship

Although there was no censorship in the GDR officially, books still had to be approved by a government body, the “Hauptverwaltung Verlage und Buchhandel”, before publication, which de facto amounted to censorship. As a rule, the book to be published had to be “reviewed” by two censors. Ironically, the censors had to be replaced by the authorities on a regular basis, as Professor Lokatis points out, because the censors eventually became “too intelligent” as a result of their work, as their socialist convictions were in danger of being compromised by American literature, for example. It is interesting, though, that all of Chandler’s novels had been reviewed by only eight people before publication in the GDR between 1967 and 1988.

All of these reviews by censors, which were euphemistically called “Druckgutachten”, had been archived as files in the “Hauptverwaltung”. After German reunification, all of these “Druckgutachten” were transferred to the “Bundesarchiv”, the Federal Archive of the Federal Republic of Germany and can still be researched there today. Historically unprecedented, the censorship of literature in the former GDR has been documented almost completely with these files.

In my conversion with Simone Menzies I realized that Chandler’s novels were as popular in the GDR as they still are all over the world. Therefore, it seems as if the reviewers rather wanted to provide justification to publish them than to ban them entirely. Thus, some reviewers emphasized Chandler’s alleged criticism of capitalism, as Klaus Schultz did in his review of The Lady in the Lake:

Socialist interpretations of Chandler’s novels

„Letztlich tut sich jedoch, für Chandler charakteristisch, eine Welt auf, die von der Jagd nach dem Dollar und vom Verfall moralischer Werte gekennzeichnet ist, und die ein Einzelgänger, Realist und Pessimist zugleich, mit gesundem Sinn für das Alltägliche und für nette Blondinen, unter Einsatz seines Lebens ein wenig zu verbessern hofft. So lieben ihn die Fans in aller Welt, so sollten wir ihn auch verstanden wissen: als literarischen Krimihelden, der sich bewußt ist, den moralischen Sumpf der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft zwar nicht trockenlegen zu können, jedoch hier und da ein wenig darin herum rühren und auf ihn aufmerksam zu machen.“ (BArch DR 1/2375 cf. Giovanopoulos p. 251)

“In essence, as is characteristic of Chandler, a world emerges that is defined by the pursuit of wealth and the decline of moral values. It is a world that a loner, a realist, and a pessimist simultaneously, with a keen understanding of the everyday and an appreciation for attractive blondes, attempts to improve, albeit at great personal risk. This is how fans around the globe admire and comprehend him: as a literary crime protagonist who realizes that he cannot eradicate the moral corruption of bourgeois society, but can incite its disturbance and draw attention to it.” (BArch DR 1/2375 cf. Giovanopoulos p. 251)

Therefore the “Druckgutachten” or reviews might be read as socialist interpretations of Chandler’s novels. I am going to write an article on those “Druckgutachten” for this blog soon. The files are classified at “Bundesarchiv”.

“Plusauflagen”: Overprinting to squeeze out the extra dollar

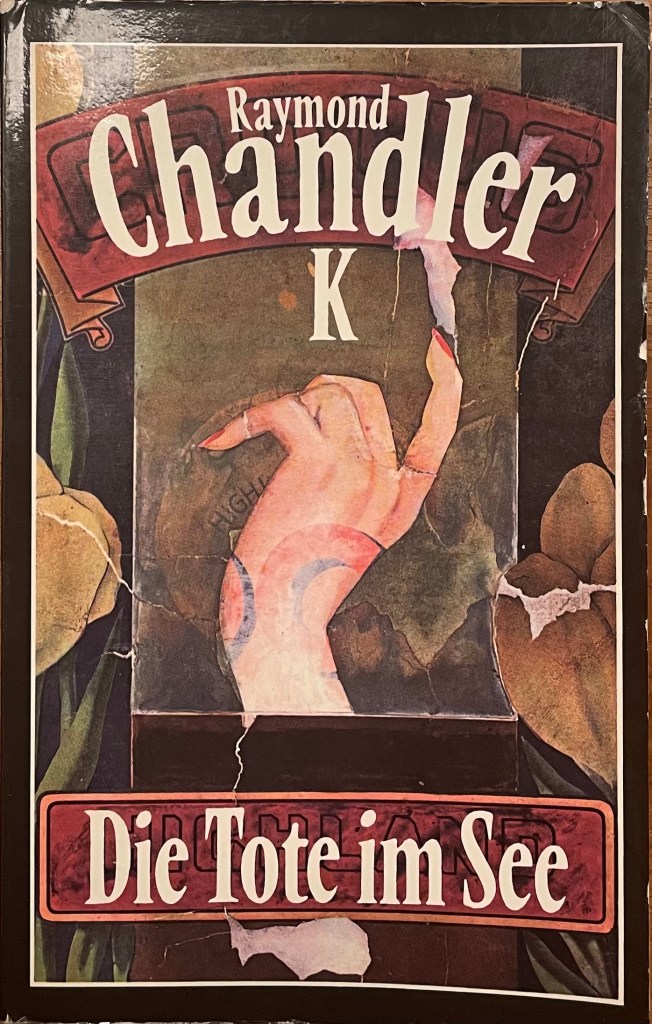

The thesis that the reviewers definitely wanted Chandler’s novels to be published in the GDR is further corroborated by the fact that the state party of the GDR (SED) tried to earn the extra dollar with Chandler’s novels, a criminal racket that is called “Plusauflagen”. The publishing houses in the former GDR illegally printed and sold more copies than had been licensed before. Chandler’s Die Tote im See (The Lady in the Lake) had been licenced for 30,00 copies, but the publishing house “Volk & Welt” illegally printed 240,000 copies. On October 7, 1990, only a few days after German reunification the publishing houses “Volk & Welt” and “Aufbau” were raided by the police, resulting in a court case. (Giovanopoulos p. 420).

“Die in der DDR erscheinende internationale Literatur von Aufbau und Volk & Welt war im Volksbuchhandel meist schlagartig vergriffen. Lizenztitel aus dem Westen wurden in weit überhöhten Auflagen gedruckt. Die 1991 aufgedeckte Plusauflagenpraxis war kriminell, verweist jedoch eindringlich auf das riesige Bedürfnis nach westlicher Literatur. So betrug die reale Auflage von Raymond Chandlers “Die Tote im See” nicht, wie im Vertrag und in offiziellen Statistiken angegeben, 30 000, sondern 240 000 Exemplare, (…). Insgesamt musste allein Volk & Welt nach 1990 Schadensersatz für zwölf Millionen illegal gedruckter Bücher an Westverlage wie Suhrkamp, Rowohlt und S. Fischer leisten. Der Profit war in die Kassen der für die Plusauflagenpraxis verantwortlichen SED gewandert, die sich an dem von ihrer Zensur aufgestauten Lesebedürfnis systematisch bereichert hatte.“ (Lokatis)

“International literature published in the GDR by Aufbau and Volk & Welt was usually sold out immediately in bookstores. Licensed titles from the West were printed in vastly inflated editions. The practice of overprinting, which was uncovered in 1991, was criminal, but it is a clear indication of the huge demand for Western literature. For example, the actual print run of Raymond Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake was not 30,000 copies, as stated in the contract and in official statistics, but 240,000 copies (…). After 1990, Volk & Welt alone had to pay compensation to Western publishers such as Suhrkamp, Rowohlt and S. Fischer for a total of twelve million illegally printed books. The profit had gone into the coffers of the state party SED, which was responsible for the practice of printing more books, and which had systematically enriched itself from the need to read that had been pent up by its censorship.” (Lokatis)

Leave a comment …