She is and has always been my favourite female character in Chandler’s entire oeuvre:

Anne Riordan. She’s cool, intelligent, pretty and autonomous.

Speir calls her “one of Chandler’s strongest, most independent, most likeable female characters.” (p. 113). In his article “Anne Riordan: Raymond Chandler’s Forgotten Heroine”, David Madden goes so far as to call her a “mirror image” of Marlowe (p. 5). Similarly, Freeman when analysing their first encounter in Farewell, My Lovely emphasizes how:

“Anne’s lines could have come out of Marlowe’s mouth. That’s how alike they are.”

Unfortunately, the character Anne Riordan was ahead of her time in the hard-boiled genre. The 1940s weren’t ready for Anne yet.

Anne Riordan never really appeared on screen

Unfortunately, I was not able find any movie stills of Anne Riordan for this article. It’s because the character Anne Riordan never appeared on screen the way Chandler intended her to be1. The character was changed to Ann Grayle in Murder, My Sweet (1944) and was even completely dropped in the 1975 film version with an aged Robert Mitchum. (Currently, I am using a picture of actress Anne Shirley here who played Ann Grayle in the 1944 movie. But maybe you can suggest a better one.) Madden explains that the character was written out of the 1975 movie simply because of Mitchum’s old age. His explanation why the character was changed in the 1944 movie, however, is elucidating:

“With Murder, My Sweet the alteration of Anne Riordan into a model of daughterly love and rectitude not only reveals the historical period and its view of young women but also demonstrates the conventions of many female depictions in the film noir genre. (…) It is ironic, then, that Chandler in 1940, in the popular genre of the detective story, created a woman who appears much more like contemporary women than these in either of these films.” (Madden, p. 10)

But fortunately times have changed for the better. Anne Riordan is the first Chandler character that comes to Freeman’s mind when she thinks about writing a hard-boiled novel with a female investigator:

“I might use a first-person female narrator instead of trying to replicate Marlowe’s voice—a woman who could help him solve the case, perhaps a character who’d already appeared in a Chandler novel. From the moment I imagined such a story, I knew who that woman would be. She was standing right in front of me, in plain sight.“

So I tried to imagine Anne Riordan being the protagonist of a modern thriller. Would she also look into the ugly face of patriarchy, like human trafficking, prostitution, rape or even femicide? So what would Anne’s sisters be like nowadays?

Pondering about these questions I read Revolverherz [The Acapulco], the first novel of German author Simone Buchholz, who incidentally used to be a free-lance journalist just like Anne Riordan, before she started writing thrillers. As a matter of fact, Buchholz does employ a first-person female narrator with a hard-boiled voice.

Hamburg noir: Chandler in St. Pauli

German weekly Der Spiegel calls Buchholz’ novels “Hamburg noir”:

“Since her debut Revolverherz (2009), Simone Buchholz has been perfecting her own genre, which could be called “Hamburg Noir”, Raymond Chandler in St. Pauli, snotty melancholy with grim humor. Every sentence is spot on. “In the past, when I still had a smooth face, I was sometimes here to work on a broken face,” says the first-person narrator, prosecutor Chastity Riley, for example, about Le Fonque, a club in Hamburg’s Schanzenviertel district, which Buchholz didn’t have to invent because it actually exists. With Riley’s tone (“Let’s drink something slow.”), the author tells of loneliness, coffee and cigarettes, of failed integration and failed love affairs; the crime plot in Mexikoring is rather incidental. Simone Buchholz loves her characters, she loves her city – the more broken, the better.”

Buchholz’ setting is Hamburg, the red-light district St. Pauli to be precise. The second biggest city in Germany provides a complex background just like the L.A. of the 1940s: Real estate agents, journalists, drug dealers, pimps, hookers, politicians, homeless people, lost teenagers, clan leaders, coffee shop owners, chefs, bankers, human traffickers, criminals, bon vivants, police officers about to retire.

Meet Chastity Riley …

Her investigator is female German public prosecutor Chastity “Chas” Riley. Riley is of Scottish-American descent, her father was an American soldier marooned in Germany during the Cold War. Riley’s first name is a rather ironic twist of a telling name, as Riley enjoys self-determined sex with different partners, very much unlike her male counterpart in L.A. And still drinks and smokes as much as Marlowe does. Marlowe and Riley both share an existentialist kind of loneliness. Both Chandler und Bucholz try to the break the tight chains of the genre, turning thrillers into what critics notoriously call “serious literature”.

… and her creator Simone Buchholz

(c) Gerald von Foris

Buchholz’s style, her prose and her sound strongly remind me of Chandler’s. You immediately like some of her characters. There are a few differences to Chandler here, though. As a public prosecutor Riley works with a team of policemen without turning Buchholz’ novels into police procedurals in the straight sense. Marlowe, however, only has one policeman who is his friend: Bernie Ohls. The other policemen usually beat him up or simply despise him (cf. my articles about hard-boiled cops on this blog).

“There is no clean side of the fast dollar.”

Just like Chandler, Buchholz castigates modern capitalist society with its obscene wealth, its obvious unequal distribution of resources and its inherent injustice.

But she also explores so-called feminist themes like femicide, rape and the oppression of girls and women in clan structures. Buchholz’ female characters can be investigators, victims and perpetrators, whereas Chandler’s murderers are most often femmes fatales.

Buchholz’ dialogues are life-like and authentic, full of witty remarks and wise-cracking. She describes her settings with an excellent eye for detail, she never fails to grasp the genius loci and evoke the right mood for the scene.

Surprisingly, these qualities of her style are definitely not lost in translation, thanks to Rachel Ward’s (no, not this one!) ingenious English version, so that the translation does not fail to impress the English-speaking reviewers either, for example Laura Wilson of the Guardian:

Or the Telegraph:

American reviewers also appreciate the hard-boiled German re-imports:

“A troubled prosecutor reconsiders her definition of justice in Simone Buchholz’s thriller The Kitchen. (…) At first, there seems to be no relationship between the victims, but when the connection reveals itself, Riley has to make important decisions about whether the system she works within is doing its job … and, if not, what she should do about it. (…) The Kitchen is a vengeance-fueled thriller in which women take power back from anyone and everyone who denies their autonomy.” (Eileen Gonzalez at forewordreviews.com)

Or the review of Hotel Cartagena …

“In Simone Buchholz’s original, stylish thriller Hotel Cartagena: during a high-stakes hostage situation in a high-class hotel bar, the past catches up to the powerful. (…) The book’s spare, staccato prose crackles with energy. Its sensibilities are neo-noir, and its wit is wry. Buchholz doles out delicious black humor: a bang “could be anything: an explosion or an explosion or possibly even an explosion.” Actions are described in a palpable, immediate manner (…). And the book’s progression is high-octane: it alternates between plot threads that appear unrelated at first, but are interwoven in a manner that ramps up the intrigue and tension. All ties together before the book’s explosive climax. (Joseph S. Pete at forewordreviews.com)

Dagger Award

Consequently, Buchholz was the first German ever to win the prestigious CMA Dagger Award for Crime Fiction in Translation in 2022.

(c) Gerald von Foris

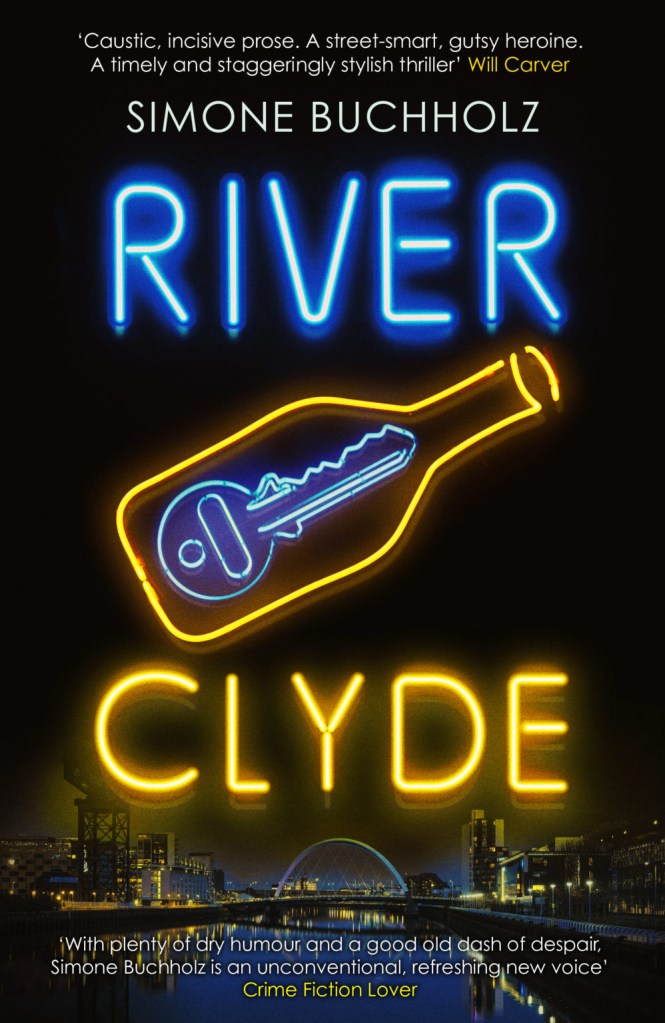

Not each of the ten Riley novels published in German have been translated into English yet. That’s why I put the covers in the correct chronological order here:

- The Acapulco (Revolverherz, 2008)

2. The Kitchen (Knastpralinen, 2010)

6. Blue Night (Blaue Nacht, 2016)

7. Beton Rouge (Beton Rouge, 2017)

8. Mexico Street (Mexicoring, 2018)

9. Hotel Cartagena (Hotel Cartagena, 2019)

10. River Clyde (River Clyde, 2021)

- I omit the character of Ann Reardon [sic] of the film The Falcon Takes Over (1942) here, because this film does not adapt a Chandler novel, neither does Philip Marlowe appear in it. ↩︎

Leave a comment …