As early as in 1949 the critic Gershon Legman claimed in Love and Death: A Study in Censorship: “Chandler’s Marlowe is clearly a homosexual – a butterfly, as the Chinese say, dreaming that he is man” (quoted in Mason p. 97). To Michael Mason The Long Goodbye is “more emphatically, even overtly a novel of homosexual feeling than any of the others” (Gross p. 92).

“Chandler’s Marlowe is clearly a homosexual – a butterfly, as the Chinese say, dreaming that he is man.”

Since Legman’s study there has been much speculation until today whether Chandler himself was queer. Legman himself even went so far as to write a letter to Chandler calling him a “homosexualist” [sic] and claiming to have found “internal evidence”, i.e. references from his novels (MacShane, Letters p. 188). Obviously, Legman was not able to differentiate between the author and his fictitious protagonist. (However, I am going to examine the “internal evidence” as presented by Legman later on.)

When Frank MacShane published the letters of Raymond Chandler in 1981, one had to acknowledge Chandler’s homophobic and downright discriminating ideas:

“I don’t deny you your right to be tolerant of homosexuality. (…) But I do think that homosexuals (…) always lack deep emotional feeling. (…) They like women who are sympathetic to them, because they are always afraid, even if they act arrogantly. Their physical bravery was proved in the war, but they are still essentially the dilettante type. Some of them, like Isherwood, are very likable, some of them are repulsive.My wife hated them and she could spot one just by walking into a roomful of people.” (MacShane, Letters p. 421

“My wife hated them and she could spot one just by walking into a roomful of people.”

In 2007 Judith Freeman (being the only female biographer of Chandler to my knowledge) further encouraged this debate by referring to her personal interviews with Chandler’s contemporaries Natasha Spender and Don Bachardy for her book The Long Embrace.

After the death of his wife Cissy and his attempted suicide Chandler’s alcoholism worsened. When Chandler was in London, Natasha Spender took him under her wing. With a group of close female friends, she formed a “rescue brigade” with one clear mission: to keep Chandler “occupied with female company”. (Freeman, p. 165).

“A strenuous repression of his own homoerotic tendencies.”

In the interview with Freeman Spender points out that these women “without a second thought” believed that Chandler was a repressed homosexual. “They thought only a strenuous repression of his own homoerotic tendencies could account for the ‘alert and vehement aversion he always went out of the way to express toward homosexuals.’” (Freeman, p. 165).

Freeman vouches for Spender’s credibility and sensitivity, given that her husband Stephen Spender had a homosexual period in the 1930s when he lived with his friends W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood in Berlin.

Left to right: W. H. Auden (1907–1973), Stephen Spender (1909–1995), and Christopher Isherwood (1904–1986), photograph album, 1930s, from the Christopher Isherwood archive. | © Don Bachardy

But Natasha Spender also recalls a luncheon with Chandler and a few friends. “At the end of the luncheon her gay friend complained to Natasha that during the meal Chandler had ‘made a pass’ at his lover. ‘I was surprised,’ Natasha said, ‘since I hadn’t noticed anything.’” (Freeman, p. 166).

“The only queer I have felt at ease with.”

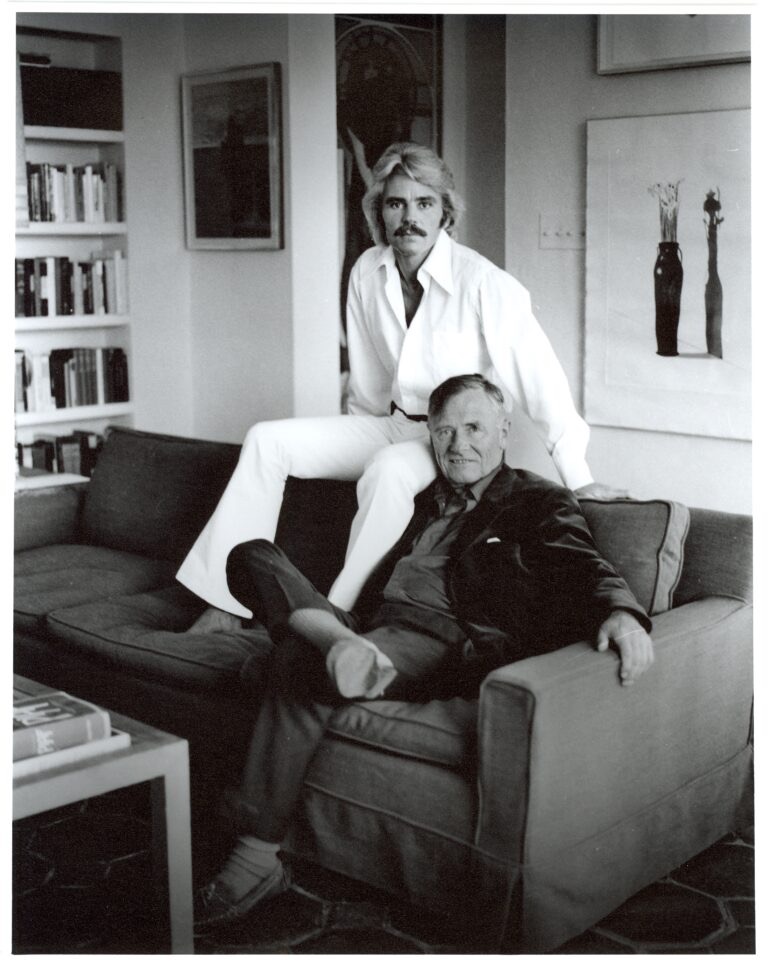

In the interview with Freeman Don Bachardy provides further confirmation of this point. He was Christopher Isherwood’s partner when they got to know Chandler in the late fifties.

(© Stathis Orphanos. Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood. Santa Monica, ca 1972.)

Chandler once wrote in a letter that Isherwood was the “only queer I have felt at ease with” (MacShane, Letters p. 416). Chandler, however, did not extend his sympathy to Isherwood’s partner Bachardy back then, as Bachardy recalls: “I did feel from Chandler that hostility toward homosexuals.” (Freeman, p. 170)

“I did feel from Chandler that hostility toward homosexuals.”

However, both Isherwood and Bachardy sensed something else: “The funny thing about Chandler is that when Chris and I first met him we both had the feeling he might possibly be gay himself.” (Freeman, p. 171)

“We both had the feeling he might possibly be gay himself.”

Not surprisingly, you can find both homophobic and – what might be considered – homoerotic references in Chandler’s novel. Most of Marlowe’s homophobic statements, however, can be attributed to the rules of the genre (cf. Madden’s Tough Guy Writers of the Thirties) as they reflect the attitude of the male working-class readers of the pulp magazines.

In The Big Sleep Marlowe finds A. C. Geiger’s body at his home which displays a “stealthy nastiness, like a fag party.” (p. 90) Hill, Jackson and Rizzuto point out that Chandler copied the queer relationship of Casper Guttmann and Wilmer Cook out of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (p. 93) and turned them into the characters Geiger and his younger lover Carol Lundgren in The Big Sleep. When Marlowe fights against Carol Lundgren, Chandler accordingly uses stock expressions like “fag” or “pansy” or macho lines like this one:

“I took plenty of the punch. It was meant to be a hard one, but a pansy has no iron in his bones, whatever he looks like.” (p. 137)

But Chandler continues describing the fight with a burlesque twist, almost comparing the two fighters to ballet dancers:

“ … for a moment it was a balance of weights. We seemed to hang there in the misty moonlight, two grotesque creatures whose feets scraped on the road and whose breath panted with effort.” (p. 138)

Marlowe’s homophobic remarks in The Little Sister are also typical of the genre as they reflect the reality or the cliches of movie industry in the 1930s. He dismisses “pansy decorators” and “Lesbian dress designers” as L.A.’s “riff-raff” (p. 188)

The Long Goodbye, however, was published years after Legman had called Chandler a “homosexualist” in 1949. This novel was a departure from the genre of the hard-boiled novel. We have to assume that Chandler deliberately inserted the following conversation between author Roger Wade and Marlowe into the text:

“Know something?” he [sc. Wade] asked suddenly, and his voice suddenly seemed much more clear. “I had a male secretary once. Used to dictate to him. Let him go. He bothered me sitting there waiting for me to create. Mistake. Ought to have kept him. Word would have got around I was a homo. The clever boys that write book reviews because they can’t write anything else would have caught on and started giving me the buildup. Have to take care of their own, you know. They’re all queers, every damn one of them. The queer is the artistic arbiter of our age, chum. The pervert is the top guy now.“ (p. 212)

“The queer is the artistic arbiter of our age, chum. The pervert is the top guy now.“

Espe“Know something?” he [sc. Wade] asked suddenly, and his voice suddenly seemed much more clear. “I had a male secretary once. Used to dictate to him. Let him go. He bothered me sitting there waiting for me to create. Mistake. Ought to have kept him. Word would have got around I was a homo. The clever boys that write book reviews because they can’t write anything else would have caught on and started giving me the buildup. Have to take care of their own, you know. They’re all queers, every damn one of them. The queer is the artistic arbiter of our age, chum. The pervert is the top guy now.“ (p. 212)

Reading these lines in 2024 one cannot help but noticing that the tone of Wade’s generalized statement closely resembles the tone of Chandler’s own discriminating ideas in his letters quoted above. Chandler’s homophobic ideas about queer critics are most probably an outlet for his deep-rooted frustration that he was never recognized as a serious writer in his lifetime. He also addresses this issue in his conversation with Ian Fleming (audio clip starting at 00:53):

“You can write a very lousy, long, historical novel full of sex, and it can be a bestseller, and you can be treated respectfully. (…) But a very good thriller writer who writes far, far better, just gets a little paragraph or so. (…) There’s no attempt to judge him as a writer.”

Puzzlingly enough, Chandler’s novels and stories also contain passages that can be called rather homoerotic – Legman’s “internal evidence”. Marlowe’s description of Red Norgaard in Farewell, My Lovely almost sounds as if Marlowe has a crush on him:

“I looked at him again. He had the eyes you never see, that you only read about. Violet eyes. Almost purple. Eyes like a girl, a lovely girl. His skin was as soft as silk. Lightly reddened, but it would never tan. It was too delicate. (…) His hair was that shade of red that glints with gold. But except for the eyes he had a plain farmer face, with no stagy kind of handsomeness.“ (p. 270)

Red Norgaard reminds Marlowe of another “soft-voiced big man I strangely liked” (p. 269): Moose Malloy. However, there are no other emotions between Red and Marlowe except companionship. Marlowe confides his deepest fears to Red when they reach the gambling ship Montecito. To me, Red’s physiognomy and his special features like “violet eyes” seem to indicate that the character Red is also symbolically charged: a kind of loving Charon, the ferryman, who does not take Marlowe across the river Styx, but back to life.

When Marlowe meets the chauffeur Shifty in The High Window he tells him: “I like small close-built men. They never seem to be afraid of anything. Come and seen me some time.” (p. 47)

In the pulp story “Pearls Are A Nuisance” it is very difficult not to regard the encounter of Walter Gage and Henry Eichelberger as a sexual one (the pun on the latter name was certainly not lost on Chandler, as he had spent a few months in Germany in 1906). First the guys flirt and have a few drinks, then they go to Walter’s apartment to spend the night together.

“He looked at me from under his shaggy blond eyebrows. Then he looked at the bottle he was holding in his hand. ‘Would you call me a looker?’ he asked.

‘Well, Henry—’

‘Don’t pansy up on me,’ he snarled.

‘No, Henry, I should not call you very handsome. But unquestionably you are virile.’

(…) ’If whiskey is what you want, Henry, whiskey is what you shall have. I have a very nice apartment on Franklin Avenue (…) I now suggest we repair to my apartment.’ (Collected Stories p. 947f.)

(…) At five o’clock that afternoon I awoke from slumber and found that I was lying on my bed in my apartment (…) I turned my head, which ached, and saw that Henry Eichelberger was lying beside me in his undershirt and trousers. I then perceived that I also was as lightly attired.” (p. 950)

Why would Chandler write such a plot in 1939 while he was still coming to grips with the hard-boiled formula and rules of the genre writing pulp stories for a penny a word? The most plausible answer for me – other than Chandler being a repressed homosexual – was first suggested by Newlin’s Hardboiled Burlesque. Obviously, it was Chandler’s way of introducing humor or what he considered humorous to hard-boiled pulp stories.

Nevertheless, all the passages quoted seem to somehow represent Chandler’s ambivalent attitude towards his own sexuality. It is, however, a fact that “in Chandler’s hundreds of personal letters there is no suggestion of gay affairs.” (Hill/Jackson/Rizzuto p. 227)

“In Chandler’s hundreds of personal letters there is no suggestion of gay affairs.”

Tom Williams offers in-depth explanation in his 2012 biography when he looks at Chandler’s youth in a public school in Britain at the turn of the century. And at what young Ray was reading at that time.

“He reached maturity in a very tightly organised public school, where sexual desires were sublimated through sport and other activity, and where chaste male friendships were encouraged and prized above all others. The English public school novel, one of the oddities of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was aimed at young men who had been through the school system. These books were sepia-tinted recreations of happy school days and, in many, the boys formed extremely close friendships that, though sexless, were loaded with romantic allusion and imagery. (…)

Ray may have missed any homoerotic subtext, taking on board their use of romantic language and the idealized relationships portrayed. This is not to say that he did not feel attraction to other men but rather that there is another explanation for his use of romantic terms to frame male relationships in his work.” (p. 163f.)

Williams comes to the conclusion that “this is the only language with which he can fully express a desire for a connection.” (p. 163)

A desire for a connection to another man. Now that’s The Long Goodbye in a nutshell.

Leave a comment …